Luxury Travel Review

Cruising Through Highlights of the British Museum

Article and photos by Scott S. Smith

London’s vast British Museum is the oldest public museum in the world

My wife and I thought we could run through a refresher on London’s British Museum when we visited for the second time in September 2016 (Great Russell Street, +44 020 7323 8000, www.britishmuseum.org, info@britishmuseum.org). We had taken a full two days 35 years before when we were last there, but figured four hours would be enough to hit the highlights. Relying on the invaluable DK Eyewitness Travel Guides London, with additional tips from Rick Steves’ Pocket London and checking the website, we boiled down the list to just the must-see-agains and some we had overlooked or which had not been on display (we belatedly discovered that only one percent of its 50,000 items are exhibited at any one time). Despite the name, this is really the greatest museum in the world on the history of the ancient world, thanks to plundering by colonial officials who had the classical education to appreciate what they brought back. As if that weren’t enough, it also has artifacts up to the present day. Established in 1753 to house a private collection, the main current building was completed in 1850, and the entire complex of 94 galleries on three levels occupies a total of 2.5 miles. We recommend to our friends visiting for the first time that they take one of the highlight tours and set aside at least one full day for the museum. To avoid crowds, we will visit weekday afternoons.

A 19th century priestly mask from the Songye people in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

We found the lower floor (basement) of the British Museum was overlooked because it is primarily devoted to Africa, while the other two floors had many world-class treasures. But African art has always been a favorite of ours when we go to any major museum of world culture. The African imagination has always struck us as astonishing, perhaps unleashed by its magical view of reality. The ritual masks, costumes, and statues are always better than anything we’ve ever seen near our home in West Hollywood, California, at the Halloween street parade, which is saying something (it draws half a million participants and spectators due to the creative contributions from movie professionals). This time, we particularly liked a multi-horned headdress for ancestral ceremonies from 19th century Nigeria and some famous bronze statues from the Kingdom of Benin.

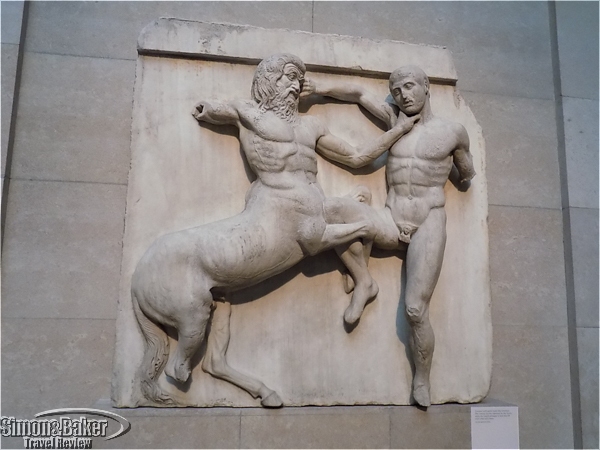

A Centaur and Lapith wrestle in a relief from the Parthenon

Back on the ground floor, we headed straight to the enormous room displaying the Elgin Marbles, décor from the Parthenon, the temple of Athena on the Acropolis in Athens, which the British brought back in 1816 and the Greeks have been trying ever since to get returned. Despite thousands of years of wear from exposure, they still showed the brilliant skills of the sculptors during the Golden Age of Greece (500-430 B.C.), the cultural supernova that led to the Renaissance and Western civilization (the best summary of their contribution is Edith Hamilton’s The Greek Way). We also saw many other gorgeous sculptures and ceramics from the Greeks and Romans in other galleries and on the upper floor.

Human-headed winged bulls from the Palace of Sargon II at Khorsabad, Assyria (near Mosul, Iraq)

The ground floor also had much from the ancient Middle East, especially Assyria. There were several sets of enormous winged-bulls that guarded the palaces of Sargon II, who reigned 721-705 B.C. and according to the Bible took the northern 10 tribes of Israel into captivity (now referred to as the Ten Lost Tribes, they were said to have “gone north” after Assyria’s fall, but may have simply blended in with other peoples in the region). One famous relief depicted the royal sport of lion hunting, and there were artifacts from ancient Jericho and Islamic cultures. More from the Middle East, especially Iran, was on the upper floors, but we just breezed through it for lack of time. The collection for the Americas was confined to two modest rooms, but had some outstanding sculptures from ancient Meso-American peoples, such as the Zapotecs. As for the rest of the floor, having been to India and Japan, and having little interest in China, we skipped the Asian section.

Coffin of Egyptian incense bearer Denytenanum, Temple of Amun, Thebes (9th century B.C.)

The upper floor’s Egyptian section may be the world’s best outside of the Cairo Museum (which we’ve been to). It is world famous for having the Rosetta Stone, carved into which was a trilingual inscription that enabled the French to begin to decipher the hieroglyphics. It was hard to photograph through the glass and the writing is tiny, but there was a model nearby we could touch. Another outstanding item was the enormous statue of Ramesses II, the 13th century pharaoh many believe was the one who reluctantly let the Israelite slaves leave Egypt. There were also numerous mummies and painted coffins.

Zapotec funerary urn from Mexico from about 200 B.C.

The other primary section on the upper level we were interested in was for Britain, covering as far back as 10,000 B.C. The most striking item was the 2,000-year-old Lindow Man, who was sacrificed in a ritual way, his skin preserved in a peat bog in Cheshire. The other big draw was the burial of a 7th century A.D. Anglo-Saxon king in a ship filled with treasures at Sutton Hoo, East Anglia, discovered in 1936. Among the many notable items, which revolutionized understanding of the era, were a ceremonial helmet, a shield, gold jewelry, silver bowls, and a lyre, a harp-like instrument. Now that we have been reminded of how incredible the British Museum is, we will not take another 35 years to return and will give it the time it needs to be fully appreciated in the future. There is a reason it is the top tourist destination in Britain.

Black Forest shop carried on with wood carved mask tradition

By Elena del Valle

Photos by Gary Cox

A display of masks at the shop entrance included a mythological figure with antlers.

There were large sculptures outside the shop.

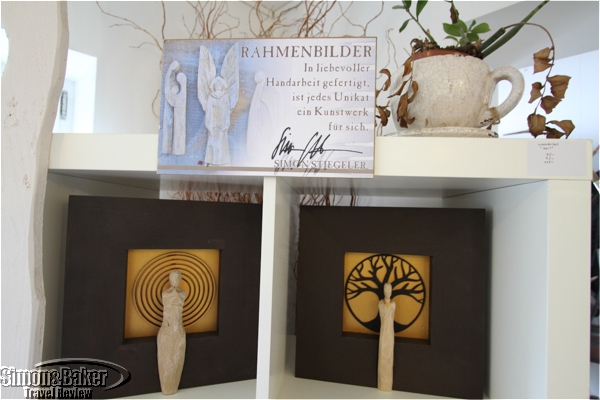

As a child Simon Stiegeler watched his parents carve traditional wood masks in their workshop in the Black Forest Highlands of Germany. As he grew older, he learned the craft in a woodcarving school in Austria and studied art in Freiburg. In time he adopted the family tradition. These days he spends his time at the Holzbildhauerei Stiegeler (Kirchsteig 5 79865, Grafenhausen, Black Forest Germany, + 49 07748-283, www.holzbildhauerei-stiegeler.de, www.holzmasken-stiegeler.de), a 100 square meter shop and workshop he owns with his family.

The masks varied from traditional designs of the region to modern adaptations.

That was where we met him, making schwäbisch alemannische fasnacht masks out of linden wood. There were witches, devils, animals, jesters and fools, some known by their local names from old words such as holzmaske, schemme, and larve. One of my favorite masks had a science fiction theme. Prices ranged from 50 to 1,200 euros.

The artist at work

“The black forest has an very old tradition in making wood masks, times ago many farmers made wood masks in the long and cold wintertime,” he said when asked about the origin of his business. “I think we are one of the last profesionell (professional) family business whitch (which) exclusively make wooden masks.”

A variety of masks hung on the walls of the workshop.

He mainly makes masks for groups, collectors, actors and special orders, he explained during our visit. In 2010, he was invited to the World Expo in Shanghai, China to present the masks as a culture ambassador for Germany.

There were other wooden items in the shop.

The artist makes masks for groups, collectors, actors and special orders.

Custom masks usually require three days, he explained. During that time he carves the mask by hand and his wife, Lillian Stiegeler, paints it. In his shop there were also modern wood carved souvenirs, especially wooden angels called flügelwesen, as well as Blackest-Forest, a house line of Black Forest themed souvenirs.

Camera bag could double as stylish briefcase

Article and photos by Aaron Lubarsky

The Tenba 15 Cooper Bag was made from a light grey canvas material with black leather accents.

The first thing I noticed about the Tenba 15 Cooper Bag (Tenba, 75 Virginia Road, North White Plains, New York 10603, +1 914 347 3300, www.tenba.com, info@tenba.com) was that it is handsome, movie star handsome. Made from a light grey canvas material with black leather accents, the minimal design is at once sophisticated and restrained. Style-wise it was a big upgrade from my bulky black Lowepro camera backpack.

I counted ten pockets

I recently put the Cooper 15 through its paces during a documentary shoot in San Francisco, California. I flew from New York, and as a carry-on bag it’s a class-act with enough exterior pockets and pouches to handle all of my needs, from a water bottle to a Kindle to a boarding pass. Tenba says the bag has “tons of pockets” but I counted ten, which was sufficient for me, including two slim expandable side pockets. The compartment for the laptop was easily accessible and just padded enough to comfortably hold my 15 inch MacBook Pro.

The bag’s interior was deceptively large.

Made in China, it’s light weight (3.6 pounds) with a peach-wax cotton canvas water-repellent exterior. The base is leather and waterproof, a feature I appreciate, although it doesn’t feel like the kind of bag that I would take out in rough weather conditions, even though it should be able to handle it.

The bag’s interior was deceptively large. Its dimensions are 15 inches wide by 11 inches tall and 6.5 inches deep. I was able to pack all of my regular gear (including sound gear) with room to spare. Surprisingly, it held as much as my larger, bulkier camera backpack. It has a removable padded camera insert, which I configured to my taste. Because the storage area is one large deep pocket, I had to stack things on top of each other. When I had a lot of items it was necessary to do a little unpacking to grab what I needed, which wasn’t ideal for run-and-gun situations.

It held as much as my larger, bulkier camera backpack.

A shoulder bag that fits in anywhere

But, I wouldn’t categorize the Cooper 15 as a run-and-gun workhorse. This is the bag I take with me to a meeting with a high-end client. It’s a shoulder bag which meant I wore it over my shoulder (go figure) or carried it like a briefcase. It has a useful trolley strap, but there were times I wanted to toss it on my back, making me miss my go-to camera backpack, which makes me look like a third grader coming home from school, but at least left both of my hands free.

I like its zen-like balance of style and function.

The only part of the design I found irksome was the top-zipper. The idea is nice: to grab my camera quickly I unzip the top of the bag and voila I should be able to reach my camera. But two layers of zippers made it cumbersome to reach my gear. Once I tucked in the interior layer I solved the problem. Another thing to keep in mind: dirt and stains showed easily on the light gray canvas. To keep this bag’s dashing appearance requires some maintenance, but it’s easy to wipe clean.

The main thing I like about this bag is the zen-like balance of style and function, appropriate for an out-of-town shoot. Even though it was designed as a camera bag, it could suit travelers without cameras who need a large, stylish briefcase. I’ll be taking it with me to my next uptown meeting.

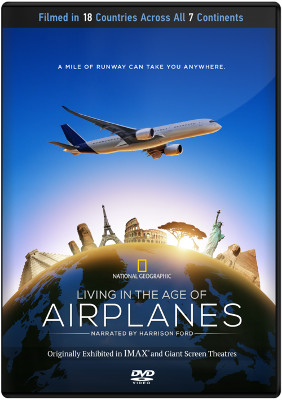

Documentary illustrates how airplane has changed world

Living in the Age of Airplanes*

For most of mankind’s 200,000 years of existence, walking was the only way to get around. Today, only 175 years after the introduction of the steam engine, airplanes are an essential way of life across our planet. In Living in the Age of Airplanes, a 47-minute film released in the United States recently, Brian J. Terwilliger, director, illustrates how the airplane has changed the world. The film is available for purchase online.

From Living in the Age of Airplanes

Narrated by Harrison Ford, a licensed pilot, and featuring arresting cinematography, the film has an original score from Academy Award winning composer James Horner, and takes viewers to 18 countries across seven continents.

Terwilliger and his crew traveled to 95 locations for the film. He has produced, directed and raised financing for three aviation documentaries. The movie was produced by Terwilliger and Bryan H. Carroll. The director of photography was Andrew Waruszewski.

*Photos Courtesy of Living In The Age Of Airplanes

Click to buy Living in the Age of Airplanes

An overnight visit to Fontainebleau, near Paris

By Elena del Valle

Photos by Gary Cox

The Gare de Lyon train station in Paris

During a spring visit to Paris, France we went on an overnight side trip to the Seine-et-Marne Department (www.turisme77.co.uk and www.paris-whatelse.com) for the first time. To get there we took a train from the Gare de Lyon in the twelfth arrondissement of Paris to Melun, a city in the Seine-et-Marne. From there we made our way around by car from the train station to the area villages where, despite cold and rainy weather, we explored museums, chateaux, an artist village, a spa, and a pastry shop, spending the night at the La Demeure du Parc, a four-star boutique hotel within walking distance from the Château de Fontainebleau (Fontainebleau Castle), a museum and former royal residence.

The rotunda inside the Château de Champs-sur-Marne looking out on the gardens

Our first stop was the Château de Champs-sur-Marne (see Eighteenth century home museum near Paris worth visit when in Seine-et-Marne area), a 16 room two story structure completed in 1708. Known for its rococo style and its Notable Gardens the former family home had been converted into a museum managed by the French government. After a guided tour in English of the Château de Champs-sur-Marne, we had lunch and a short guided tour in English of the Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte, a private estate open to visitors and my favorite attraction overall. Even when compared with grand former royal residences the property’s historic character, artistic harmony and beauty stood out. Before leaving and despite the ugly weather we made our way around the beautiful gardens in an abbreviated self-guided exploration.

Les Bains de Marrakesh in Fontainebleau

The shop at Les Bains de Marrakesh

Before checking into our hotel we had a massage at Les Bains de Marrakech (186 rue Grande, 77300 Fontainebleau, +33 09 81 13 17 21, lesbainsdemarrakech.com, fontainebleau@lesbainsdemarrakech.com). Because we arrived late our massages were cut short. Despite that the staff members were friendly and welcoming. The small facility was spotless and quiet.

The war memorial in Barbizon

The house of Robert Louis Stevenson

Dinner (and breakfast the following morning) at our hotel was excellent. In the morning, we met Véronique Villalba, our English speaking guide in front of the Fontainebleau Castle, a former residence of the French monarchy, for an excellent tour. Following lunch, we headed to the charming artist Village of Barbizon, about seven miles northwest from Fontainebleau. We walked around with umbrellas in hand, exploring the touristy main street and admiring the pretty facades. We popped into Le Musee des Peintres de Barbizon (the Museum of Painters of Barbizon). Although it was crowded at times we enjoyed our visit thanks to our guide’s insights and engaging discussion.

Tasty treats at Frédéric Cassel, Fontainebleau

On our way back to our hotel we stopped at Frédéric Cassel Fontainebleau (71-73, rue des Sablons, 77300 Fontainebleau, +33 01 60 71 00 64, www.fredericcassel.com), a shop in the town’s popular pedestrian shopping street for espresso, tea, chocolates, and pastries. We had a Vanilla Millefeuille and an Ilanka pastry, a worthwhile sweet ending to our pleasant visit, before our taxi drove us back to the small train station, where we boarded the crowded train back to Paris.

We unexpectedly loved Victoria and Albert Museum, especially for its sculpture collection

Article and photos by Scott S. Smith

The north side of the John Madejski Garden courtyard at the Victoria and Albert Museum

In September 2016, my wife, Sandra, and I reluctantly visited the Victoria and Albert Museum, VAM, (Cromwell Road, +44 020 7942 2000, www.vam.ac.uk, contact@vam.ac.uk) in the South Kensington area of central London, United Kingdom. We were hesitant because we normally don’t care for decorative art, but Time Out London had rated it the number one attraction of a city packed with world-class destinations. We had flown in that morning and planned to go to our hotel to sleep off our jet lag before heading to the museum, which was open until 10 p.m. on Wednesdays. But our hotel was out of the way and we decided to head directly to the museum for a few hours. It had one of the world’s largest and best collections of its kind, with 4.5 million objects, only a tiny fraction of which could be displayed at one time in its 145 galleries spread over seven miles on six levels. They included ceramics and glass, textiles, furniture, sculpture, metalwork, drawings, photos, jewelry, and costumes from around the world covering 5,000 years.

It was founded in 1852, the year after the Great Exhibition, a world’s fair that showed off the fruits of the industrial age and provided the museum’s initial collection. First called the Museum of Manufactures, it was the world’s first devoted to “applied art and science,” and the official opening at the current location was overseen by Queen Victoria in 1857 (her last public appearance was in 1899 at the laying of the foundation for a new building).

Samson Slaying a Philistine by Giovanni Bologna

Walking into the central sculpture hall on the ground floor we were greeted by the dramatic marble statue of Samson Slaying a Philistine by Giovanni Bologna (also known as Giambologna) dated about 1562. He was sculptor to the Medici dukes of Tuscany and the most important one after the death of Michelangelo in 1564, until the emergence of Gian Lorenzo Bernini in 1614. Renaissance works dominated the long room. The VAM had one of the most comprehensive sculpture collections from the post-Classic era, with 22,000 from around the world created between 400 A.D. to 1914, using materials ranging from wood to bronze.

Glazed glass basin from Turkey

Islamic art was represented with 19,000 objects, one of the world’s largest collections, with works from the 7th to 20th centuries. We were particularly impressed with the rugs and tile art, with the artistry honed for nearly a millennium within the mandate of not depicting human or animal forms (except in the Persian Shiite tradition). We saw that up close on the Taj Mahal in India and in Uzbekistan, where floral and abstract forms were perfected. The VAM lighting in that area made it difficult to take photos, but we did get one of a glazed glass basin from Iznik, Turkey, 1545, with the Golden Horn design (a reference to the waterway off Istanbul). Some believe the museum’s glass and ceramics collection of 80,000 to be the most comprehensive in the world.

Tibetan deity representing enlightenment

With 160,000 items, the Asian collection may be the largest in the West. We only saw a small part of it, but particularly loved the exquisite gilded brass statuette of the donkey-headed, many-armed Tibetan Buddhist deity Kharamukha Samvara, a metaphor for enlightenment in the Tantric tradition of channeling sexual energy. The male aspects represented compassion, the female wisdom.

Boy with Bagpipes by Caius Cibber

We visited the room with the Raphael Cartoons, sketches for tapestries displayed in the Sistine Chapel on special occasions. By that time we were exhausted and our last photo was of the statue of a boy playing the bagpipes with his dog at his feet, sculpted from Portland stone by Danish artist Gaius Gabriel Cibber in 1680. Cibber moved to London in the 1650s, where he worked closely with the legendary architect Christopher Wren. When we return to London, the Victoria and Albert will be high on our list so that we can explore the areas we breezed through and check out those we completely neglected on photography, books, furniture, costumes, and jewelry, as well as regional exhibits on Asia and the Americas. I would recommend the VAM to friends who like art museums, regardless of whether they think they will like the focus on decorative arts.