by Editor | Jul 8, 2013 | Attractions, New Articles

By Elena del Valle*

The interior of the Palais Garnier

For years we had wanted to attend an operatic performance at the Palais Garnier, the old opera in Paris, France. We had enjoyed one at Opera Bastille, the modern theater across town, and longed for the exuberant historic building’s greater intimacy. On our last visit to Paris we managed with no small amount of effort to obtain good seats in the ninth arrondisement building. La Cenerentola was one of a few operas performed in the theater that season and happily for us one that we liked.

Marianna Pizzolato (Angelina)

Claudia Galli (Clorinda), Nicola Alaimo (Dandini), Bruno De Simone (Don Magnifico), Marianna Pizzolato (Angelina), Maxim Mironov (Don Ramiro) et Anna Wall (Tisbe)

By the time we checked for tickets online several months in advance of our strip nearly all shows were sold out. Luck was on our side for a performance on a Sunday at 2:30 p.m. On the day of the three hour event, the weather was clear. We enjoyed a plentiful brunch prior to our arrival at the Palais.

The three sisters in La Cenerentola

I was thankful that we arrived in a good mood. When we went to pick up our tickets at the window we encountered a long line. Worse yet we discovered the opera cashier was unable to accept any of several credit cards we offered making it necessary for us to pay in cash. Once inside, the lines for the coat check and the restroom were so long we avoided both. This meant no food or beverages during the intermission. And we were forced to carry our sweaters and coats as we strolled along exploring the beautiful halls of the old building.

A scene in La Cenerentola

The ceiling of the Palais Garnier

On the plus side, the interior of the theater was as pretty as we anticipated and the musical event was worthwhile on its own. While a few glitches detracted from the experience overall we were rewarded with an outstanding performance by the Bayerische Staatoper from Munich accompanied by the Orchestre et Choeur de l’Opera National de Paris.

*Photos of La Cenerentola courtesy of Opéra national de Paris/ Ch. Leiber and of the Palais Garnier by Gary Cox

by Editor | Apr 29, 2013 | Attractions

By Elena del Valle

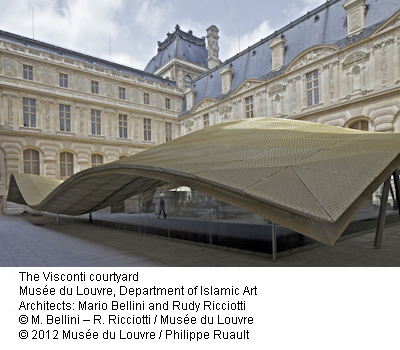

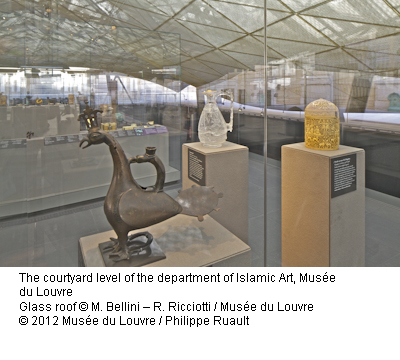

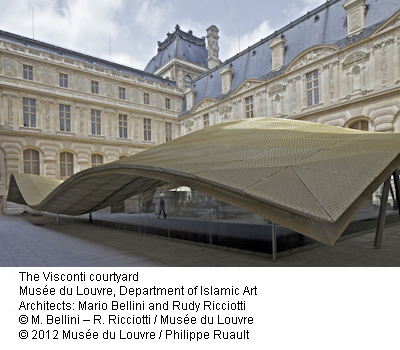

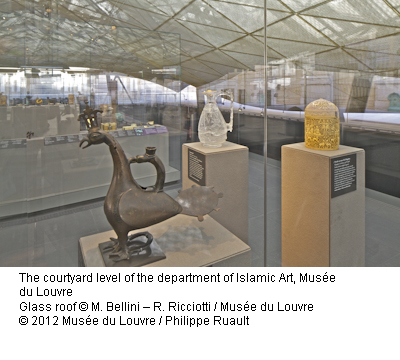

In September 2012, the Louvre Museum in Paris, France opened the Islamic Art Galleries with much fanfare. The iconic museum’s new wing is home to 18,400 objects, 3,000 of which were on display at the time of our visit. The majority of the items, 15,000, was part of the museum’s collection before the galleries were established. The remaining 3,400 works were on permanent loan from the Musée des Arts Décoratifs.

Because the interior buildings of the former palace were full the decision makers opted to enclose courtyard space to exhibit the Islamic art. They claimed 3,000 square meters of space for the new galleries, much of it had been formerly outdoors. The project, led by architects Mario Bellini and Rudy Ricciotti, began in 2001 and took 11 years to complete. It was the first major project of the museum in many years. The galleries form the eighth department at the Louvre. At the time of this writing, the other departments are Egyptian Antiquities; Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Antiquities; Near Eastern Antiquities and Eastern Mediterranean Provinces of the Roman Empire; Prints and Drawings; Decorative Arts; Paintings; and Sculptures.

In 2012, 9.7 million people visited the museum. An estimated 650,000 of those visited the new wing since it opened last year. Exceptional items in the new wing highlighted in museum educational materials include: carved teak Door panel from the Dar al-Khilafa, Samarra; Pyxis of al-Mughira, a round casket carved of elephant ivory; Ewer from the treasury of Saint-Denis, made of carved and polished rock crystal; a stucco Princely head with traces of color; Monzón lion, a molded and engraved bronze lion; Baptistery of Saint Louis, made of copper alloy engraved and inlaid with silver, gold and black paste; a gilded and enameled Bottle with a coat of arms; a stone-paste Peacock dish; and Dagger with a horse-head hilt made of Damascus steel inlaid with gold, jade, rubies, emeralds and kundan gold.

In 2011, the budget for the entire Louvre was 210 million euros. A little more than half, 55 percent, was from public subsidies, and 45 percent came from the museum’s own revenue generating sources. In contrast, 98.5 million euros were necessary to make the Louvre’s new Islamic wing a reality.

The French government supplied 31 million euros and the museum used 11.5 million of its own resources. A whopping 56 million euros were donated by foreign governments, and private donors. The lion’s share, 26 million euros, was provided by four foreign governments or their monarchs: Mohammed VI, King of Morocco; Sheik Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah, Emir of Kuwait; Qabous Bin Said Al-Said Al Said, Sultan of Oman; and the Republic of Azerbaijan. The remaining 30 million euros were contributed by private individual donors, companies and foundations. Principal among those was the Alwaleed Bin Talal Foundation. The Total Foundation contributed 6 million euros and Lafarge 5.4 euros. View a recent detailed article on the Louvre Museum in the Simon and Baker Travel Review.

by Editor | Apr 22, 2013 | Accomodations, Attractions, Ecotourism, New Articles

Article and photographs by Chester Godsy and Joni Johnson-Godsy

Wildebeest and zebra gathered for the river crossing

Our first visit to Kenya coincided with the well known wildebeest migration. We were delighted to have an opportunity to spend a full day watching the animals gathering on the northern side of the Mara River, preparing to cross into the southern portion of the Maasai Mara Reserve during our stay at Elephant Pepper Camp. Part of the Cheli & Peacock portfolio, the nine-tent 160-hectare property offered a perfect combination of camping luxury in an intimate setting with the backdrop of classic Africa.

Our tent at Elephant Pepper Camp

by Editor | Apr 15, 2013 | Attractions, Audio, Food

By Elena del Valle

Photos by Gary Cox

Cyril Lignac in the kitchen at Le Quinzieme Cyril Lignac

The week after dining at Le Quinzieme Cyril Lignac in the southwest corner of Paris we went across town to Cuisine Attitude (10 cité Dupetit Thouars,75003 Paris, France, +33 1 49 96 00 50, fax +33 1 42 56 15 46, www.cuisineattitude.com, ecole@cuisineattitude.com), a cooking school owned by Cyril Lignac, the restaurant owner and executive chef of Le Quinzieme, where we attended the first part of Christmas Petits Fours, a cooking demonstration with some student participation. While at the cooking school I had an opportunity to speak with the chef in English. We extend a special thank you to him for agreeing to a short English language interview. Click below to listen to our conversation.

Aude Rambour, executive chef, Groupe Cyril Lignac

The executive chef demonstrating macaron assembly

After a brief welcome and introductions Aude Rambour, executive chef, Groupe Cyril Lignac, prepared the dessert dishes with the assistance of her staff. She explained the steps in French while a small group of French students observed. At times, she invited one or more of the students to take turns trying some of the steps. During the morning session, she prepared four desserts: Almond and dry fruits macaroons; Chocolate truffles, passion fruit; Candied chestnuts, light Bourbon vanilla cheese cream; and Tainori dark chocolate tart, Yuzu sorbet.

The teaching kitchen at Cuisine Attitude

Although the French language four hour program on holiday desserts was dynamic and fast paced, it was challenging to understand what was happening without any English language translation from the staff. We had understood someone would translate but the entire demonstration was conducted in French. A company representative informed us recently that an American chef has joined the group and is available to translate the sessions for English speakers.

by Editor | Mar 11, 2013 | Accomodations, Attractions, New Articles

Article and photos by Chester Godsy and Joni Johnson-Godsy

Looking out at the bush from Kitich Camp

In the 1920s, Martin and Osa Johnson traveled from the United States to remote places in Kenya and brought back stories, films and photographs that helped define the American idea of the African safari. Their book entitled I Married Adventure helped peak our curiosity about the mountainous region in Kenya north of Nairobi. It was exciting to imagine that on our trip we were recreating part of their journey nearly one hundred years later.

A Samburu warrior in traditional dress

The Samburu people of Northern Kenya live much the way they did back in the days of Martin and Osa Johnson. A Samburu village lies only a couple of miles from Kitich Camp, a walking safari tented camp part of the Cheli & Peacock portfolio, where we stayed on our trip to Kenya. Lamario, one of our guides, took us to this village and helped us bridge the gap between languages and cultures. The Samburu people we met were warm, curious and inviting. Only a few white skinned people had been to the village before us so curiosity was mutual. Visiting this village gave us insights into a time when a community was more important than an individual.

The dining area at Kitich with photos of local Samburu on the walls

A young woman in the village invited us into her home, where we spent time with her and asked her questions about the Samburu lifestyle and culture. We saw the creative ways they live in harsh, arid conditions. We learned about their lives, values and culture. We came away in awe of these people. We had an experience we will treasure for a lifetime.

The pool at Joy’s Camp

From there we made our way southeast to Joy’s Camp, its sister property in the Shaba National Reserve still north of Nairobi. Named for Joy Adamson, a well-known naturalist, artist and author, the camp offered comfortable accommodations dramatic views and good wildlife sightings as well as access to the nearby Samburu National Reserve.

Part of the common areas at Joy’s Camp

by Editor | Feb 18, 2013 | Attractions, Food and Wine, New Articles

Article and photos by Josette King

The Courtyard of the Nobles of Berckheim in Riquewihr is an early stone house and turret with sundial

In France, La Route des Vins (The Wine Road) wends its way north to south from Marlenheim (near Strasbourg) to Thann (near Mulhouse) through 170 kilometers (106 miles) of the rolling hills of the Alsatian vineyard. Along the way it reaches over half of the 119 wine-producing villages, with the remainder only a short drive away.

Riquewihr is recognized as one of the most beautiful villages in France for its picturesque medieval architecture

While Alsace traces its viticulture history back to Roman times and many of the villages along La Route des Vins can charm visitors with picturesque architecture reaching back to the Middle Ages, the itinerary itself is a contemporary concept. Intent on rejuvenating Alsatian tourism and refocusing attention on its once famed wine industry, both devastated by the Second World War, the regional tourism office organized an automobile rally on May 30, 1953. All participants departed at the same time, half from Marlenheim and the other half from Thann. Along the way they enjoyed a number of wine tastings and tourist site visits before reaching each other. History doesn’t seem to have recorded which team managed to travel the farthest, but the event proved to be a major success. Thus, La Route des Vins was born. Today, over two million visitors per year come from all corners of Europe and beyond to enjoy the warm welcome of the wine-growing community. Many return time and again to sample the superb wines and gastronomy of the region (paté de foie gras and choucroute garnie originated here).

Every break in the roofline offers a glimpse of the vineyards

I was recently one of these return visitors, when I was able to couple a trip to Colmar, the lovely self-appointed capital of the wine road, with a long overdue stop in the nearby village of Riquewihr. It was les vendanges (wine harvest time), and I looked forward to taking a walk up the hill beyond the city walls to the venerable Schoenenbourg Vineyards, reputed since the Middle Ages for producing some of the finest Riesling in the world, and where grapes are still picked by hand. I also planned a leisurely stroll through the historic village with its narrow cobblestone streets lined with centuries-old half-timbered houses. But most of all, I wanted to return to the Hugel & Fils winery (3, rue de la première armée, 68340 Riquewihr, France, +33 (0)3 89 47 92 15, fax +33 (0)3 89 49 00 10, http://www.hugel.com, info@hugel.com), and pay a quiet homage to the memory of a man who almost four decades ago kindled my interest for good wines. Jean Hugel had hosted my first wine tasting in the very cellar where I was now headed. Along with the basics of wine appreciation, he taught me a golden rule by which I still measure wines today.

The Hugel Winery headquarters and cellars below

“A good wine,” Jean Hugel told me, “is one that you enjoy when you drink it, still appreciate when you pay for it, and can remember fondly when you wake up the next morning.” He was at the time at the head of Hugel & Fils, one of the most prestigious labels in Alsace, and a family that traces its wine making tradition back 12 generations, to 1639. I was saddened in the summer of 2009 to read his obituary in The New York Times, where he was memorialized as “a leading force in resurrecting the Alsatian wine trade.” I could only nod, and remember his passion as he introduced me to the peerless Hugel Rieslings and Gewurztraminers and most exquisite of all, the nectar-like Vendange Tardive (late harvest) wines. These prestigious wines are made in tiny quantities from overripe grapes picked well after the classic vintage, and in the best years only. These grapes have been affected by botrytis cinerea (a fungus commonly known as pourriture noble, or noble rot). Jean Hugel is credited with writing the rules for the production of Vendange Tardive, which became law in 1984. To this day, no matter where in the world I happen to be, I can never see one of the green fluted bottles with their iconic yellow Hugel label without remembering my host on that long ago afternoon.

A passing wine harvest truck shows me the way to the Hugel Winery

On the day of my visit, his nephew Etienne Hugel welcomed me to Riquewihr with the same warmth and enthusiasm. Alas, the weather was not so friendly. A cold drizzle had been falling since morning; not a propitious day for a walk to the Schoenenbourg. We headed for the cellars instead, under the meticulously preserved 16th century building of the Hugel headquarters. Along the way, we stopped by the dock where trucks were pulling in with their precious cargo of plump white grapes in plastic tubs. These were immediately brought to the press house, quality tested and selected before being tipped through a funnel designed to gravity-feed them into one of the pneumatic presses on the floor below. The free-run and first pressing juices are then directed, again by gravity only, into stainless-steel vats where they settle overnight to remove solids before the fermentation process begins (Hugel uses only these for its own label. The last pressing is always set aside and sold in bulk). The juice is then gravity-fed into giant oak casks, some over 100 years old, or into stainless steel vats for fermentation.

The Sainte Catherine cask dates back to 1715 and is still in use today

Wine tasting with Etienne Hugel

We continued on, farther into the cellar that reaches deep and wide under the old town. Wines mature there in rows upon impressive rows of huge casks, including the famous Sainte Catherine dating back to 1715, and still in use, before ending our tour in the tasting room. Etienne takes us on a seven-wine graduated tasting with the same verve as his uncle did so many years ago. By the time we get to the Gewurztraminer Jubilee 2008 and the divine Gewurztraminer Vendange Tardive 2005, both from the oldest plots of the Hugel estate in the heart of the Sporen grand cru area, I am ready to break all the rules of wine tasting: I sip, and I swallow. I am certain that Jean Hugel would approve