by Editor | Nov 11, 2013 | Accomodations, Ecotourism, New Articles

By Laura Scheiber

Photos by Matthew Harris

Chiawa Camp

My husband and I had high hopes that Chiawa Camp, a tented property in Zambia‘s Lower Zambezi region, would provide us a premiere safari experience based on the property’s awards and recognition. Soon after our arrival we discovered the camp, situated on a picturesque riverbank in the Lower Zambezi National Park, offered outstanding game viewing, luxury camp accommodations, and excellent cuisine and service. We also learned that Chiawa had another side. Its founders, Dave and Grant Cumings, a father and son team, participated in the fight against poaching. While staying at the camp, we had a chance to chat with Grant about how it all began.

Back in the day, Dave used to take his son Grant on bush trips, exploring east along the Zambezi River. Eventually they arrived at Chiawa’s current location and found themselves going back for repeat trips. Sleeping under the stars and surrounded by amazing wildlife and geography, they believed the spot to be a magical place, and wanted to share it with others. They started taking friends and family on trips to the area. In time, the practice evolved into photo safaris with diplomats living in Lusaka. Through some convincing and lucky contacts, the governmental parks department awarded Dave and Grant a permit to build a semi permanent camp in the Park.

Grant Cumings, co-owner, Chiawa Camp

At first things were difficult. Zimbabwe is just on the other side of the river, and the civil war saw a lot of guerrilla activity in the region long before Chiawa’s existence. Soldiers from both sides would frequently fight on the Zambian side of the river. Eventually the conflict ceased, leaving a number of former soldiers in possession of firearms. With few opportunities to earn an income, many turned to poaching. Grant spoke poignantly of seeing his first butchered elephant as a young man, something that moved him deeply and motivated him to fight passionately for conservation.

The Cumings father and son team started to move against poachers, working with scouts to track, capture and turn them over to the authorities. It was dangerous work. To their dismay they uncovered evidence of corruption, which strongly suggested that some officials were in collusion with the poachers. On one occasion, Dave brought in a detective from Lusaka to break the poaching ring. A number of poachers were found and captured, and used rifle shells were gathered as hard evidence of poaching activity. However, the day after capture a detective said the shells had mysteriously been misplaced.

It quickly became apparent to them that the poachers had bought him off. Dave thought quickly on his feet, and in a moment of inspiration, responded that losing the shells was no problem since he had some extras (which wasn’t true). That tricked the detective into thinking that the prosecution would go ahead. During a tense showdown, the detective “found” the missing shells and the prosecution was able to proceed.

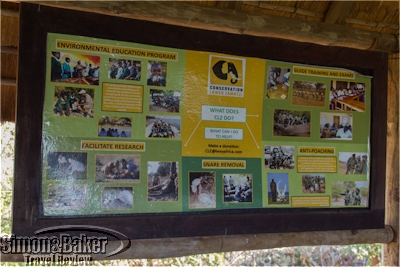

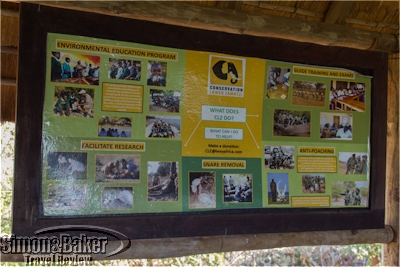

The Conservation Lower Zambezi Environmental Education Program

At the height of poaching, Grant and his team might come across 60 to 70 mutilated elephants each year, whereas now they might come across six to seven carcasses in the bush, most of them from animals that had died of natural causes. Grant and his father realized that capturing poachers was only half the story, education was also key. If poachers and the children of poachers could be made to understand that keeping those beautiful animals alive was worth more in the long run than killing them, then conservation efforts would be sustainable.

Through a serendipitous meeting with a Danish ambassador who drove into Chiawa Camp one day, Grant was able to secure Danish sponsorship and establish the Conservation Lower Zambezi Environmental Education Program.

A residential center, he explained, it strives to provide a wide variety of conservation and HIV/AIDS education to Zambians from all over the country. It also hosts the rigorous guide certification exams. The program, he said, has provided career opportunities for many locals, some of whom now work as guides at Chiawa. Grant explained that although poaching remains an ongoing battle to this day, it has significantly declined in the region thanks to the efforts of the Cumings family members and park scouts, and subsequently through Conservation Lower Zambezi, a charity they co-founded and of which Grant is a trustee and past chairman.

A bulletin board at the Conservation Lower Zambezi facilities

Grant’s conservation efforts are not yet done. His dream is that one day the black rhino might be introduced back into the Lower Zambezi National Park. He’s resigned to the fact that this isn’t possible just yet because they would present too tempting a target for the poachers. His hope is that over time this will change, through continued education and anti-poaching efforts.

It was a pleasure to meet Grant, an inspirational pioneer of conversation in the Lower Zambezi region. While we thoroughly enjoyed our luxury safari experience at Chiawa, what made it special was understanding firsthand the ethos of conservation that is so intricately intertwined in the history and current practices of the camp. We hope to one day return and see its continued conservation efforts evolve to preserve the natural beauty of the Lower Zambezi National Park.

by Editor | Oct 28, 2013 | Accomodations, Ecotourism, New Articles

By Laura Scheiber and Matthew Harris

Photos by Matthew Harris

Crossing the Luangwa River

We arrived at the bank of the Luangwa River, at the end of a game viewing drive in Zambia’s South Luangwa National Park from our previous safari lodge. After loading our luggage into a small boat, we were ferried across the river by one of our hosts, Finlay Hunter. On our arrival at Chinzombo, a luxury safari camp, Finlay and his wife and cohost, Wendy offered us cool washcloths to freshen up, served us fruit cocktail drinks and made us feel at home. It was a sign of things to come. The young, energetic, professional and attentive couple went out of their way to ensure our stay was perfect.

View of the Luangwa River from the dining area of Chinzombo camp

The camp, on the Luangwa riverbank opposite the beautiful South Luangwa National Park, is a one hour drive from Mufwe Airport, which is a quick hour flight to Lusaka. Being close to the national park meant that we were able to enjoy great game viewing drives and walks with our charismatic guide Shaddy Nkoma. With years of guiding experience, he provided fascinating insight into the African bush. He also regaled us with stories of his youth in Zambia including having to swim to school through crocodile infested rivers. One time he even lost his clothes in the process.

Our room with a pool view

The newly opened camp was a joy for us as guests. The architecture was modern with a nod to safari camps of old, with leather, wood and brass fittings. The handsome open bar and dining area also had a section of paraphernalia from the late Norman Carr, a safari industry veteran. In it were some wonderful prints of him with two male lions he raised from cubs.

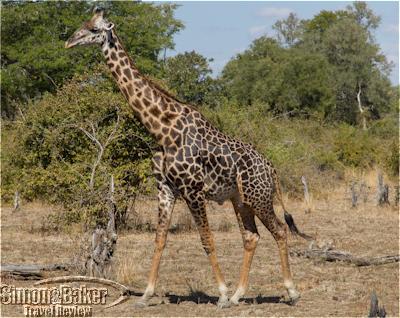

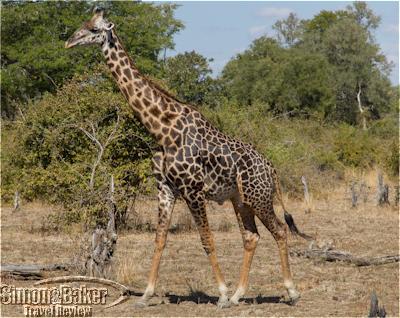

A giraffe we saw on a drive from Chinzombo camp

Our open fronted luxury tented accommodations with a personal plunge pool and views out onto the Luangwa River were superb. Amenities that made us feel pampered included bathrobes, slippers, hot water bottles the staff placed in our bed during the evening room service, and complimentary drinks in the fridge.

River viewing from the couch

The cuisine at the camp was delicious, fresh and plentiful. We especially enjoyed the sundowners and cakes served on safari drives. It was a wonderful way to watch the sunset. Chinzombo had the feel of a modern luxury boutique hotel with safari influences and access to the amazing African bush at its doorstep. We thoroughly enjoyed our contemporary safari experience.

by Editor | Apr 22, 2013 | Accomodations, Attractions, Ecotourism, New Articles

Article and photographs by Chester Godsy and Joni Johnson-Godsy

Wildebeest and zebra gathered for the river crossing

Our first visit to Kenya coincided with the well known wildebeest migration. We were delighted to have an opportunity to spend a full day watching the animals gathering on the northern side of the Mara River, preparing to cross into the southern portion of the Maasai Mara Reserve during our stay at Elephant Pepper Camp. Part of the Cheli & Peacock portfolio, the nine-tent 160-hectare property offered a perfect combination of camping luxury in an intimate setting with the backdrop of classic Africa.

Our tent at Elephant Pepper Camp

by Editor | Aug 20, 2012 | Attractions, Ecotourism

Photos by Gary Cox

Seasonal plant displays in the entrance hall

When our contributors visited Cape Town earlier this year they spent a morning at the Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden

A clear view of the cape flats

Although they were caught by a downpour before they could complete their explorations they had much positive feedback. Click here to read about their visit to the 538-hectare estate with a 36-hectare garden that will celebrate its centenary anniversary next year.

by Editor | Jun 25, 2012 | Attractions, Ecotourism

By Elena del Valle

Photos by Gary Cox

The cliff walk offered dramatic views of the ocean and cliffs

One of my favorite walks in South Africa is in the Western Cape. During our last visit to Hermanus we would walk the Cliff Path Nature Area daily for a couple of hours enjoying the stunning vistas and hoping to spot a whale, any whale even if it was not whale viewing season. Just as the sun was about to rise we would walk from Birkenhead House, a small hotel in Voelklip, west through the residential area of Kwaaiwater into central Hermanus on the marked and guarded (by uniformed security company staff) path which hugged the coast for miles, part of the Fernkloof Nature Reserve. During our walks, we saw a variety of coastal plants and birds, dassies (said to be a tiny relative of the African elephant), teenage seals and unexpectedly two brides whales which, according to the townsfolk, were a rare sighting.

Shy little birds were out at first light

Occasionally small markers would point the way and large IFAW (International Fund for Animal Welfare) signs would provide information about the flora and fauna of the area including, of course, the whales that Hermanus is famous for nationally. In addition to the signage there were rubbish bins and indications that someone in the municipality cleaned and managed the path on a regular basis. We also noticed designated parking areas at various places that intersected the walkway.

The waves constantly smashed into the rocky islands and shoreline

Seals climbed onto the rocky islands

The path passed steps below the rear terrace of our hotel and continued past Hermanus along the coast. We found it ideal to depart just before sunrise. Earlier than that and it was difficult to see the unlit path clearly, risking a twisted ankle or fall, and loosing out on of some of the beauty of the scenery for lack of light. Much later than sunrise was less worthwhile in part because the bird viewing and photography light were best early in the morning. From a comfort perspective as the sun emerged the light quickly became harsh and, although the ocean breeze was pleasant, the summer sun was punishing causing us to tire prematurely.

Small colorful flowers brightened the fall landscape

Along the way, benches were scattered at strategic spots where we could stop to enjoy the sea views. From the cliffs we could observe the crashing waves, copious quantifies of sea kelp, a variety of birds and coastal views of the upscale area. Adjacent to the walk there were beautiful houses in varied styles and sizes and as we neared the town there were some small buildings too.

A dassie family perched on the rocks

We often crossed paths with locals out for a walk or jog, sometimes in the company of their unleashed dogs. Most of the paved walkway was built within a natural area surrounded by greenery and flowering plants passing through beaches, up cliffs and across bridges. There was a less attractive segment that veered inland on a sidewalk for a few minutes along the well trafficked main road before returning to the waterside and reaching central Hermanus. On Marine Drive, in the central part of town and across the street from the bay, we discovered Yves’s Pudding & Pie (87 Marine Drive, +27 082 924 0920), an informal spot to stop for a quick savory bite and cold beverage. We especially liked the pies.

by Editor | Apr 23, 2012 | Accomodations, Attractions, Ecotourism, New Articles

Article and photos by Josette King

Hoatzin birds were a frequent sight near the lodge

“Stop, stop!” I sputter, too excited to keep my voice down. Fabian, the local park ranger who is paddling, doesn’t speak English but he gets the idea and brings the canoe to a smooth halt. Roberto, my Ecuadorian guide who speaks English fluently, looks at me askance. He has just pointed out a large bird perched in the dense jumble of rainforest. It looks like a chicken with too much turquoise eye shadow and a bad hair day. “The bird,” I exclaim. “Yes, it’s a hoatzin,” he reiterates matter-of-factly. He clearly fails to grasp the importance of the moment. So does the bird, which has by now been joined by two of its friends. They are engaged in a croaky argument while heartily tucking into the foliage. I feel compelled to explain that on a previous Amazon visit, a thousand miles downriver from here, I had once spent a whole week, including a half-day hike in the waterlogged underbrush, in search of a hoatzin. And I had only managed to hear its distinctive cry and ponderous take off as it vanished into the forest canopy. “We have lots of hoatzins here,” Roberto assures me after I have photographed these to my heart’s content, and for good measure a rare rufescent-tiger heron that has been observing the proceedings from a nearby stump.

The king size bed was draped in mosquito netting

We resume our slow way upstream under an arch of tangled mangroves and palms, along the narrow channel that connects the Napo River, one of the most important tributaries of the Amazon, to Anangucocha Lake. We are in the heart of 21,400 hectares (82 square miles) of conservation land located on the ancestral territory of the Kichwa Anangu community, in the northwest corner of Ecuador’s Yasuni National Park. The park is a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve regarded by scientists as one of the most bio-diverse areas on the planet. Several notable sightings later, including a tree-toed sloth and my first ever monk saki monkey, we reach the lake. On its far side, the shore is dotted with the thatched-roofed, bright ocher adobe bungalows of the Napo Wildlife Center luxury eco-lodge.

My bungalow had a shaded terrace overlooking the lake

Set into some of the most pristine rainforest environment I have ever visited, the lodge is designed to meet the high expectations of international tourists for wilderness accommodations. It features attractive bungalows with private terraces overlooking the lake, modern bathrooms, round the clock electricity and WiFi connection throughout the property. Strategically located observation towers at the lodge and in the forest offer a unique perspective of the abundant wildlife around the lake and above the forest canopy. My wildlife viewing is exceptional, not only for its abundance and variety but because of the excellence of the guiding. At the lodge, guides come in pairs: a bilingual, state-licensed guide and a native Yasuni Park-licensed ranger who also acts as a local guide, sharing his knowledge of plants, medicinal plants and Kichwa traditions. One evening, they take me on a nighttime canoe ride in the swamps near the lodge, with a special spotlight to view nocturnal creatures.

Coffee was served around the clock in the main hall

Beyond the excellence of accommodations and wildlife viewing opportunities, a highpoint of my visit is the opportunity to observe first hand the positive impact of the Napo Wildlife Center on the daily life of the Anangu people. The lodge and conservation land are wholly owned and managed by the Kichwa Anangu community. They are the keystones of a far-reaching program to improve the quality of life of the people and preserve the integrity of their ancestral territory and culture while providing them with sustainable employment. Most of the staff comes from the community. Their pride in the Napo Wildlife Center is palpable, and translates into warm and attentive service. Additionally, while the life of the community is separated from tourism activities, one hour downstream from the lodge, I see women welcome guests to the Interpretation Center facility adjacent to their village. It is especially rewarding to be able to connect with them (with Roberto as interpreter) as they introduce me to the tasks of their daily lives as well as their traditional Kichwa crafts and dances.

An Amazon forest dragon

I am gratified to hear of the rigorous sustainable tourism practices implemented by the Napo Wildlife Center program. Profits are reinvested within the community, with education and healthcare as major priorities. The center also returns a share of the annual profits to each family and provides a stipend to the elderly. To limit the lodge’s impact on its environment, it has implemented an environmentally sustainable sewage system, with waste waters treated to high standards before being released into the swamps. Trash is kept to a minimum and composted whenever possible. What is safe to burn is burned and buried, with the remainder transported to designated landfills outside the park. And these practices have been extended to the Anangu community at large, for a cleaner, healthier living environment.

A striated heron

The Napo Wildlife Center is also engaged in a strong anti-poaching program, with its conservation land patrolled by community rangers employed and equipped by the lodge. The Napo Wildlife Center was recognized in 2009 with the Rainforest Alliance Community Sustainable Trend Setter Award, and the Best Jungle Lodge Award from the Latin American Travel Association at the World Travel Market in London, U.K. And it is becoming a model for other sustainable tourism community projects throughout Ecuador.

The banks of the Napo River were a tangle of dense rainforest

And by the way, Roberto was right. We came across so many hoatzins during my four-day visit that by the time I left, I barely spared them a glance. Visit the Simon & Baker Travel Review to read more about my stay at the Napo Wildlife Center.