Cruising Through Highlights of the British Museum

Article and photos by Scott S. Smith

London’s vast British Museum is the oldest public museum in the world

My wife and I thought we could run through a refresher on London’s British Museum when we visited for the second time in September 2016 (Great Russell Street, +44 020 7323 8000, www.britishmuseum.org, info@britishmuseum.org). We had taken a full two days 35 years before when we were last there, but figured four hours would be enough to hit the highlights. Relying on the invaluable DK Eyewitness Travel Guides London, with additional tips from Rick Steves’ Pocket London and checking the website, we boiled down the list to just the must-see-agains and some we had overlooked or which had not been on display (we belatedly discovered that only one percent of its 50,000 items are exhibited at any one time). Despite the name, this is really the greatest museum in the world on the history of the ancient world, thanks to plundering by colonial officials who had the classical education to appreciate what they brought back. As if that weren’t enough, it also has artifacts up to the present day. Established in 1753 to house a private collection, the main current building was completed in 1850, and the entire complex of 94 galleries on three levels occupies a total of 2.5 miles. We recommend to our friends visiting for the first time that they take one of the highlight tours and set aside at least one full day for the museum. To avoid crowds, we will visit weekday afternoons.

A 19th century priestly mask from the Songye people in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

We found the lower floor (basement) of the British Museum was overlooked because it is primarily devoted to Africa, while the other two floors had many world-class treasures. But African art has always been a favorite of ours when we go to any major museum of world culture. The African imagination has always struck us as astonishing, perhaps unleashed by its magical view of reality. The ritual masks, costumes, and statues are always better than anything we’ve ever seen near our home in West Hollywood, California, at the Halloween street parade, which is saying something (it draws half a million participants and spectators due to the creative contributions from movie professionals). This time, we particularly liked a multi-horned headdress for ancestral ceremonies from 19th century Nigeria and some famous bronze statues from the Kingdom of Benin.

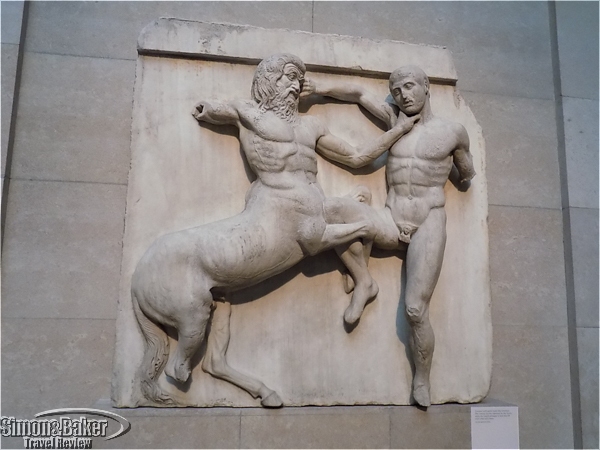

A Centaur and Lapith wrestle in a relief from the Parthenon

Back on the ground floor, we headed straight to the enormous room displaying the Elgin Marbles, décor from the Parthenon, the temple of Athena on the Acropolis in Athens, which the British brought back in 1816 and the Greeks have been trying ever since to get returned. Despite thousands of years of wear from exposure, they still showed the brilliant skills of the sculptors during the Golden Age of Greece (500-430 B.C.), the cultural supernova that led to the Renaissance and Western civilization (the best summary of their contribution is Edith Hamilton’s The Greek Way). We also saw many other gorgeous sculptures and ceramics from the Greeks and Romans in other galleries and on the upper floor.

Human-headed winged bulls from the Palace of Sargon II at Khorsabad, Assyria (near Mosul, Iraq)

The ground floor also had much from the ancient Middle East, especially Assyria. There were several sets of enormous winged-bulls that guarded the palaces of Sargon II, who reigned 721-705 B.C. and according to the Bible took the northern 10 tribes of Israel into captivity (now referred to as the Ten Lost Tribes, they were said to have “gone north” after Assyria’s fall, but may have simply blended in with other peoples in the region). One famous relief depicted the royal sport of lion hunting, and there were artifacts from ancient Jericho and Islamic cultures. More from the Middle East, especially Iran, was on the upper floors, but we just breezed through it for lack of time. The collection for the Americas was confined to two modest rooms, but had some outstanding sculptures from ancient Meso-American peoples, such as the Zapotecs. As for the rest of the floor, having been to India and Japan, and having little interest in China, we skipped the Asian section.

Coffin of Egyptian incense bearer Denytenanum, Temple of Amun, Thebes (9th century B.C.)

The upper floor’s Egyptian section may be the world’s best outside of the Cairo Museum (which we’ve been to). It is world famous for having the Rosetta Stone, carved into which was a trilingual inscription that enabled the French to begin to decipher the hieroglyphics. It was hard to photograph through the glass and the writing is tiny, but there was a model nearby we could touch. Another outstanding item was the enormous statue of Ramesses II, the 13th century pharaoh many believe was the one who reluctantly let the Israelite slaves leave Egypt. There were also numerous mummies and painted coffins.

Zapotec funerary urn from Mexico from about 200 B.C.

The other primary section on the upper level we were interested in was for Britain, covering as far back as 10,000 B.C. The most striking item was the 2,000-year-old Lindow Man, who was sacrificed in a ritual way, his skin preserved in a peat bog in Cheshire. The other big draw was the burial of a 7th century A.D. Anglo-Saxon king in a ship filled with treasures at Sutton Hoo, East Anglia, discovered in 1936. Among the many notable items, which revolutionized understanding of the era, were a ceremonial helmet, a shield, gold jewelry, silver bowls, and a lyre, a harp-like instrument. Now that we have been reminded of how incredible the British Museum is, we will not take another 35 years to return and will give it the time it needs to be fully appreciated in the future. There is a reason it is the top tourist destination in Britain.